The Byzantine churches in Constantinople were stripped of their ornaments after the city was taken by the Ottomans on 29 May 1453. Many of these churches now lack their mosaic decoration and their rich liturgical ornaments. In contrast, in Ravenna the Italian city on the shores of the Adriatic that was a capital of the Exarchate, there are several Byzantine churches whose decoration is preserved almost intact. Ravenna was for three centuries like a neighborhood of Constantinople.

The importance of Ravenna as a city dates from the time of Honorius, son of Theodosius. Believing he was unsafe in Rome, then threatened by barbarians, Honorius moved his court to Ravenna. At the time of Honorius in Ravenna were built several important buildings, but the only building that retains intact its mosaic decoration is the rich mausoleum of his sister Galla Placidia. We already discussed Galla Placidia’s Mausoleum in a previous essay. The time of Honorius and Galla was followed by a construction hiatus in Ravenna during the barbarian irruption, until the city regained again its splendor as Byzantine metropolis during the reign of the Ostrogoth Theodoric and the subsequent Byzantine occupation.

After the Byzantine re-conquest of Ravenna, the city became the capital of an exarchate with jurisdiction over southern Italy, Sicily, the northern coast of Africa, and Spain. It was at this time that Ravenna was enriched with new monuments that still can be seen to this day. The main church of Sant’Apollinare still stands in the city as well as other church dedicated to Sant’Apollinare, in the place of the old port, two wonderful baptisteries, and the wonderful church of San Vitale.

The Great Basilica of Sant’Apollinare intramuros (inside the walls) was initially dedicated to St. Martin and consecrated in 504. It was called, for a period of three centuries, Church of St. Martin with Golden Sky because its roof was golden. But when in 856 the basilica located at the port and where the body of St. Apollinare was worshiped (that is the present church of Sant’Apollinare in Classe) was sacked by the Saracens, the body of the patron saint of Ravenna was relocated to the church of St. Martin and this church then changed its name to Sant’Apollinare Nuovo to distinguish it from the old church of Sant’Apollinare at the port or in Classe.

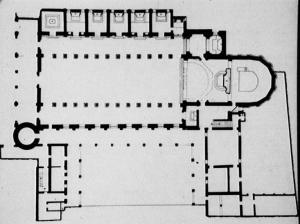

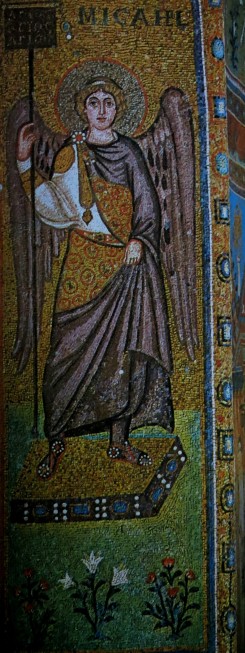

The Sant’Apollinare Nuovo floor plan is of a Latin-type basilica*: three naves separated by rows of columns with the central nave covered by a wooden roof and the lateral naves covered by vaults. The capitals of the columns separating the naves are decorated with thorny acanthus completely different from the classical style capitals of the Roman basilicas, and between the capital and the arches have the trapezoidal abacus replacing the architrave and that we already mentioned, this structure is called the pulvinus. The mosaics located over the columns of the central nave are famous. They develop on each side of the central nave as a procession of parallel figures: on one side are the saints and martyrs led by St. Martin who come to worship the Savior; on the other side are the saint women and virgins preceded by three angels and the Wise Men, who come in a long procession towards the image of the Madonna and Child who is resting in her lap. Both, saints and virgins, are dressed in the Byzantine style. It is clear that these mosaics are the work of Eastern masters of the mosaic.

The other church dedicated to Sant’Apollinare in Classe (meaning at the site of the former port of Ravenna) was built in 534 and completed eight years later. It has three naves separated by columns, very similar to those of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, with thorny acanthus capitals and trapezoidal abacus*; above, instead of the frieze with saints and virgins, the mosaics have some medallions with portraits of the bishops of Ravenna. This decoration has almost disappeared. Only the mosaics of the apse are conserved, with a large cross standing in the middle of a flowery field and sheep guided by St. Apollinare; also there are figures of the bishops of Ravenna located in the apse’s cylinder, between the windows, and at the top there is a clypeus or medallion with the bust of Christ and the four apocalyptic symbols of the Evangelists. A flowery field surrounds the figure of St. Apollinare with its green turf filled with small trees, flowers, and birds.

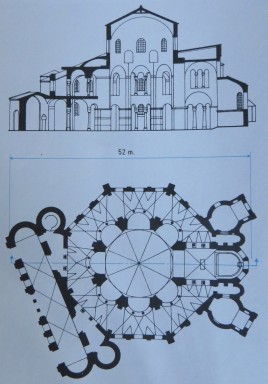

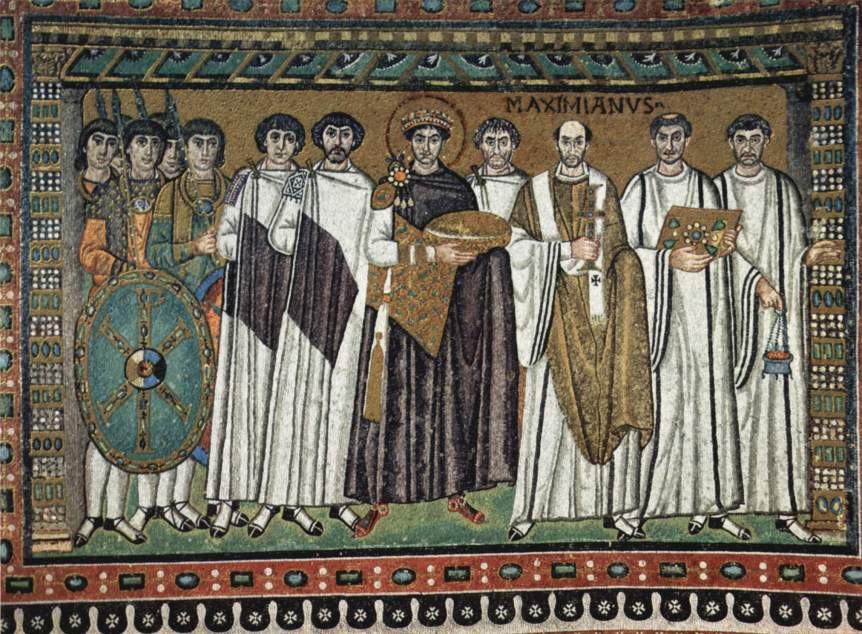

The last major Byzantine building in Ravenna is the church dedicated to St. Vitale. It remains almost intact, although some mosaics were left unfinished and some others were destroyed during the Renaissance. The floor plan of St. Vitale has all its elements surrounding a central dome supported by pillars and columns. The naves around the central dome are covered with a combination of vaults which penetrate one another in an irregular fashion. The apse has the only mosaics that have not been destroyed. Trees, flowers, plants, and animals, on golden background, decorate the ceiling, and sometimes are interrupted by small medallions with images of prophets and Apostles. At the base of the apse there are friezes with historical figures. On one side is the Emperor Justinian offering gifts to the new church accompanied by the Bishop Maximian alongside barons, priests, and warriors. In the front frieze his wife, Empress Theodora covered all over with jewels, also offers a magnificent vessel amid a brilliant group of court ladies and eunuchs of her entourage, there are also hanging curtains, a fountain, and background buildings.

Other mosaics of San Vitale reveal the influence of Syrian themes such as rocky landscapes, while the central figure of the apse is typically Latin: Christ seated on the universe represented by a blue sphere and still portrayed as the beardless young man as he was represented earlier in the Roman catacombs. How different is this Christ of Ravenna from the typical Byzantine Pantocrator* represented a few centuries later in Hagia Sophia at Constantinople! In Hagia Sophia’s mosaics, Christ is portrayed as a mature character, with a thick black beard revealing strength and power.

____________________

*Abacus: A flat slab forming the uppermost member or division of the capital of a column, above the bell. Its chief function is to provide a large supporting surface, tending to be wider than the capital, to receive the weight of the arch or the architrave above.

*Abacus: A flat slab forming the uppermost member or division of the capital of a column, above the bell. Its chief function is to provide a large supporting surface, tending to be wider than the capital, to receive the weight of the arch or the architrave above.

*Basilica or Latin basilica: (From the Latin word basilica, derived from Greek meaning, “serving as the tribunal chamber of a king”). The word was originally used to describe an ancient Roman public building where courts were held, as well as serving other official and public functions (like a town hall). The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the main forum. By extension the name was applied to Christian churches which adopted the same basic floor plan and it continues to be used as an architectural term to describe such buildings, which form the majority of church buildings in Western Christianity.

*Basilica or Latin basilica: (From the Latin word basilica, derived from Greek meaning, “serving as the tribunal chamber of a king”). The word was originally used to describe an ancient Roman public building where courts were held, as well as serving other official and public functions (like a town hall). The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the main forum. By extension the name was applied to Christian churches which adopted the same basic floor plan and it continues to be used as an architectural term to describe such buildings, which form the majority of church buildings in Western Christianity.

*Pantocrator or Christ Pantocrator: In Christian iconography, Christ Pantocrator refers to a specific depiction of Christ. The most common translation of Pantocrator is “Almighty” or “All-powerful”. In Medieval eastern roman church art and architecture, an iconic mosaic or fresco of Christ Pantokrator occupies the space in the central dome of the church, in the half-dome of the apse or on the nave vault. Some scholars consider the Pantocrator a Christian adaptation of images of Zeus, such as the great statue of Zeus enthroned at Olympia.

*Pantocrator or Christ Pantocrator: In Christian iconography, Christ Pantocrator refers to a specific depiction of Christ. The most common translation of Pantocrator is “Almighty” or “All-powerful”. In Medieval eastern roman church art and architecture, an iconic mosaic or fresco of Christ Pantokrator occupies the space in the central dome of the church, in the half-dome of the apse or on the nave vault. Some scholars consider the Pantocrator a Christian adaptation of images of Zeus, such as the great statue of Zeus enthroned at Olympia.

4 thoughts on “Golden Age of Byzantine Art III: Churches of Ravenna -Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Sant’Apollinare in Classe, and San Vitale-”