After the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) involving Sparta (Dorians) against Athens (Ionians) for the supremacy in Greece, the Greek cities which formed the Peloponnesian League welcomed several artists from Athens. By those times, in some Greek cities were built several circular buildings called tholos*, like the building of the Mysteries in Samothrace, the Philippeion in Olympia and the so called “lantern of Lysicrates” in Athens with its elegant crowning, decorated with acanthus leaves.

However, despite the Dorian triumph, Athens continued to maintain the artistic supremacy in Greece thanks mainly to its sculptors, although the artistic trends significantly changed. The monumental sculptural decoration of the temples’ pediments was no longer necessary, and the bronze sculpture was replaced by exclusively marble sculpture. The topics also changed: the main gods were no longer exclusively represented, but where slowly replaced by the gods who had more contact with humans such as Aphrodite, Love, the deities of fields and forests, or intellectual personifications (allegories*) like the symbolic figures of Virtue, Peace and Democracy. Individual portraits began to multiply and instead of the type of the winner athlete, or charioteer, or runner, the sculptors represented dramatic poets or orators. The triumph at the stadium was succeeded by the successes of the forum*.

As for the sculpture, several disciples of Phidias continued his style throughout the fourth century BCE. Among the disciples of Phidias were: Kresilas, Callicrates, Callimachus, Alcamenes… But to understand how the teachings of Phidias passed from one generation to another, the most striking example is that of a family which during four generations transmitted from parents to children the secrets of the art of sculpture. This dynasty, we could say, begun with a first master named “Praxiteles the Elder”, a colleague of Phidias, perhaps somewhat older, but that worked with him on the Acropolis. His specialty was bronze casting. It is believed that one of his works was a Hera or Juno, from the temple of Plataea, which apparently was the original inspiration for many later Roman copies. This Hera has one foot firmly on the ground, while the other is slightly backwards, thus giving the body a balancing posture frequent in Greek statues of the V century BCE. This type of Hera must have served as a model for the colossal statue to which the famous head of the Ludovisi collection belonged to.

From Praxiteles the Elder learned his son Kephisodotos from whom one work is certainly known: the group of Eirene and Ploutos, the two personifications of Peace and Wealth. Both the old Hera attributed to Praxiteles and the Eirene of Kephisodotos had no major change in the composition of types, but were reminiscent of the style of Phidias: the figures leaning on their left foot thus defining the straight folds of their robes at that same side, while the right leg slightly bents thus marking the inclined lines of the statue. The more tender, more delicate and more sensitive expression in these statues is what placed them apart from the types established by Phidias, a feature that characterized this new style.

But the transcendental revolution took place in the school of Athens by the great masters of the second generation after Phidias, especially Kephisodotos’ son, named after his grandfather Praxiteles. He was the artist of elegance and sensuality. His works included the Faun (which was located in Athens), Love (in Thespis) and his famous Satyr.

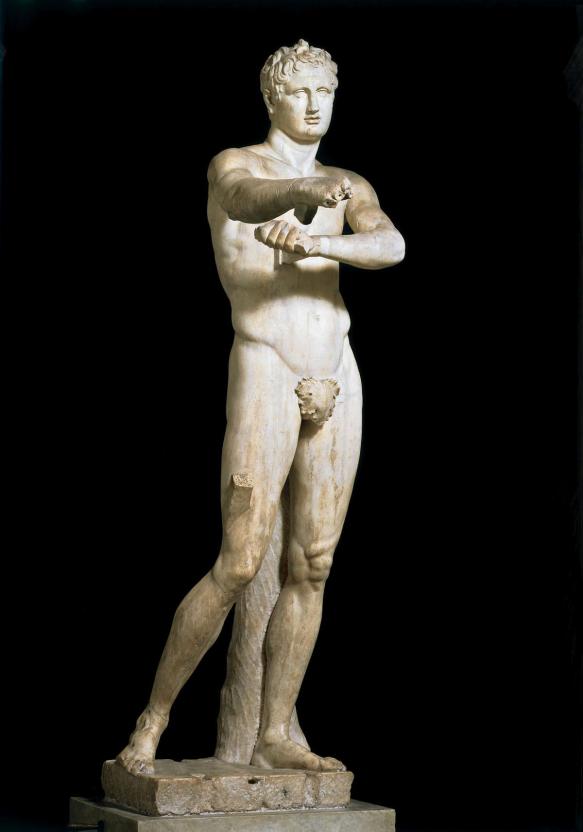

This statue of the Satyr was very famous in antiquity: it was the most reproduced sculpture by Roman copyists. It portrays a young man with an indolent posture leaning on a tree trunk with his feet crossed and an arm resting on his hip. In the Satyr of Praxiteles his forms are rounded, no muscles are accentuated neither in the arms nor the legs, his torso is almost feminine, a folded lynx fur gracefully covers his chest. But the most interesting is his head; in his eyes and mouth there is a faint animal expression in human form. The goat’s ears are hidden by the profuse hair, but his cloudy look denotes what the true nature of the model is, in which intelligence seems to have been replaced by instinct. Another famous sculpture by Praxiteles is the young Apollo, known as Apollo Sauroktonos because it has been shown in the act of killing a lizard perching on a tree trunk.

But the work of Praxiteles most prized in antiquity was his nude statue of Aphrodite which was in Knidos. Until then, the goddess of love had always been represented wearing some type of clothing. Praxiteles portrayed her naked, in the moment right after finishing her bath: on one side has a jug with perfumes and a folded blanket to wrap herself. Like all works of the great master, it appeared slightly polychrome: soft color in the eyes, lips and hair, the rest of her body would have a waxy patina. The Aphrodite of Knidos has been recognized in several Roman copies, the best is kept in the Vatican. The figure leans on one foot, the other leg, bended, makes no effort (in a contrapposto*). For this reason, and with the aim of keeping the balance of the marble block, there is a mechanic need of the pedestal represented by both the jug and the blanket.

Other marbles attributed to Praxiteles are the group of Hermes and Dionysus in Olympia. Hermes holds in his left arm the little Dionysus, while with his right hand shows the boy a bunch of grapes that the child tries to reach. The figure of Hermes is supported on a large robe hanging from his left arm which actually makes the figure more stable and somewhat inclined.

Another work of Praxiteles is a base with reliefs that supported one of his statues in Mantinea. It represented the Muses and Marsyas playing the flute. The third work of Praxiteles is the head of the young Eubuleos (which means good leader or good counselor), found in the ruins of the sanctuary of Eleusis, which could well be mistaken for one of the busts of the Florentine sculptors of the Renaissance.

The morbid style of Praxiteles was preferred for the funerary statues. Many female figures wrapped in large robes were idealized portraits to be placed in a tomb. Two of these statues (called the large and small herculanenses because they were found in Herculaneum) are the best examples of this type of portraits. Of equally Praxitelian influence is a statue from Knidos in the British Museum. Critics want to see her as Demeter, the mother goddess. It is very likely that the alleged “Demeter of Knidos” is nothing more than a funerary portrait, an idealized portrait of a real person used to decorate her own grave.

Among the disciples of Praxiteles was his son, the fourth family sculptor, named Kephisodotos after his grandfather. To Kephisodotos the Young has been attributed the called Fanciulla or girl of Anzio. For some people represents not a priestess, but a young male teenager whose robe of cult acolyte gives him an effeminate appearance. The figure has the hair collected on his forehead and nods with religious devotion on the tablet where the laurel branch and purification instruments are. His body is covered by a heavy woolen mantle which encircles the waist and exposes one shoulder.

Another disciple of Praxiteles, Leochares, made a group of Ganymede abducted by the Eagle, one co[y is now in the Vatican Museums. From the same Leochares was supposed to be the famous Apollo Belvedere which rather should be attributed to another pupil of Praxiteles, the Corinthian Euphranor. However the Apollo Belvedere, so estimated by the Romantics of the 19th century, is thought to be a copy of an oldest original. Another twin statue of Apollo Belvedere is Artemis or Diana of Versailles in the Louvre. Both gods, Apollo and Artemis, advance moving their bodies forward and are balanced by the position of their arms.

It is natural that the favorite types of Praxiteles were repeated for a long time. However, the type of nude Aphrodite was not immediately accepted. The goddess was most often depicted with a blanket covering her legs. So are those of Arles, Milo and Capua.

The Aphrodite discovered on the island of Melos or Milo, now in the Louvre, shows clear influences of the style of Praxiteles. It is now considered a work of the late second century BCE. The Aphrodite of Milo stands leaning on one foot while the other rested on a kind of step (in contrapposto). One arm was slightly holding the folds of the robe that covered her legs. It has been said and speculated that her other arm was holding the apple for the judgment of Paris.

Another great master sculptor of the fourth century was Scopas, as great as Praxiteles. His thoughtful sadness contrasts with the aesthetic optimism of Praxiteles. But even in resting figures Scopas reflected his intensely dark spirit. We know several mutilated copies of his statue of Meleager, the young hunter preparing to leave for the hunt of the Calydonian boar which ended to be fatal for him. He is represented as if before leaving he had a premonition of his approaching death. The sublime expression of the Phidian types has been replaced by this pathetic silence of moral pain. The mythological subjects were also interpreted as a symbol of human tragedy. Scopas represented the Homeric heroes suffering the eternal anguish of our own soul like Socrates and Plato did. Scopas temperament was suitable for large works of architectural decoration. He was the last great master who devoted himself to decorate the triangle of a temples’ pediment.

A significant index of the spirit of this time is that the most conspicuous monument of this period is a grave: the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. The construction of this monument involved sculptors as talented as Scopas, Briaxis, Timothy and Leochares. It is a building that was built as a tomb for the Kinglet or satrap of Caria, Mausolus and commissioned by his wife Artemis. This work was among the seven wonders of the world and had as a base a high plinth topped by 36 columns. The monument ended in a pyramid of 24 steps, and at the top at 140 feet was the marble chariot sculpted by Pityo. This colossal work, built on the shores of Asia for a satrap subdued to Persia, and for which many Greek artists worked together indicates the expansive force of the Greek art during those times.

Scopas and Leochares worked together for the sculptural decoration of the mausoleum. The topics represented in these reliefs were still the favorite of the Athenians: the famous battle with the Amazons and a chariot race with charioteers wearing long flowing robes. However, the giant statue of Mausolus, who together with Artemis was in the chariot at the top, is attributed to Briaxis. The most interesting part of the figure of Mausolus is his head, with his hair floating backwards, giving him a barbarian air.

Finally, we have to talk about the last great master sculptor of the fourth century, who dominated with his powerful personality all the generation following Scopas and Praxiteles. This was Lysippos, the favorite sculptor of Alexander the Great, the only one who had the privilege to sculpt his official portraits. Lysippos, after Phidias with his glorious idealism, Praxiteles with his morbid sensuality, and Scopas with his tragic obsession, represents another stage of the ancient Greek art: the high naturalism.

Alexander was the great model of this dynamic and naturalistic sculptor. Countless heads of Alexander have survived with his abundant curly hair during the days of his glorious adolescence, or fatigued with his hair loops disorganized as if he was a sun god. Lyssipos brings personality and character to portraits even in the case of a semi-divine hero as Alexander was.

After Alexander, the favorite topic of Lysippos was Hercules, son of Zeus, the prototype of the hero for the intellectuals of the fourth century. Lysippos represented him in his labors (the 12 labors of Hercules).

With Lyssipos, the Athenian sculpture begun to represent figures that had what we call “three dimensions”. Before Lysippos, perhaps with the exception of Myron, all sculptors assumed that their images will be seen from a certain point of view, and so they composed figures to do their best effect from that particular side.

Lysippos is the first who emancipated his statues from the spectator: many of his figures can be seen from different sides. The statues called Apoxyomenos (“the one who cleans himself by scraping”) represents a young runner removing oil and dust from his arms with a small brass instrument. This new type of athlete differs completely in its proportions to the Doryphoros and other oldest athletic statues. The body is more flexible and nervous. Although he is engaged in gymnastic exercises, this young man belongs to a more refined society. The head is much smaller and more naturally expressive. He extends his arms forward forcing the spectator to look at him by its side in order to appreciate what he is doing.

Inspired by the style of Lysippos, especially for his proportions and body posture, is the Ares Ludovisi, a figure of the warrior god carelessly sitting with legs forward and his hands resting on his left knee. As the god of war, in his leisure he was prone to love, so the Ares Ludovisi has a small cupid playing between his feet, this cupid has been restored (the face is from the Baroque sculptor Algardi), but it is certain that it was in the original sculpture.

The influence of the art of the great Athenian masters of the fourth century is seen in the numerous tombstones of this period. The cemetery of Athens was located in the suburbs of the city and decorated tombs were on each side of the main roads leading to the country side through the suburbs of the “Ceramic” neighborhood. Generally, they consisted of a small architectural base topped by small constructions with a commemorative relief. It is likely that Athens had specialized workshops for this kind of monuments.

These tombstones represented an idealized portrait gallery, a kind of overview of the enlightened society of Athens in the fourth century. The tombstones preferably represented tender family scenes in the moment relatives had to be separated from the deceased, all in placid privacy, disturbed only by a slight shade of sadness. The dead usually sits to better indicate the impression of repose; individuals of his/her family surround him/her while one of them takes his/her hand affectionately. Other times the dead woman says goodbye for the last time to the jewels that once had adorned her body while a young servant opens the little ark in which the jewels were jealously guarded. These steles frequently repeated favorite topics, in this regard they followed the general law of the Greek art which held to a small number of types. These types were not only reproduced, but were altered when they were interpreted by different artists. However, some tombstones departed from the common types and became very personal.

At the same time that the interest for the great monumental art decreased, painting also descended from the decorative frescoes to easel paintings. The evolution of Greek painting was faster than that of sculpture. Note that the great master painter Polygnotus (the artist of the great frescoes of Delphi, Athens and Plataea) also did paintings on little wood boards.

The topics and style of these paintings varied profoundly. We are familiar with the work of two famous painters of the first generation after Phidias, the rivals Zeuxis and Parrasio.

Parrasio delighted in detailing the highest degree of expression and character of his figures, both in their physiognomy and gesture. This was heavily criticized as much as the unexpressive coldness of the characters portrayed by Zeuxis in his paintings. His Theseus, too tender, seemed to be “fed with roses”. We have written descriptions of a painting of one of the disciples of Parrasio, Timanthes. It depicted the sacrifice of Iphigenia and was admired in antiquity by the way the characters expressed pain. Agamemnon appeared veiled to hide his desperation as a father, the other heroes of the Trojan War vividly expressed their feelings: Ulysses, Menelaus, Nestor. Atop was Diana with a deer, which had to replace Iphigenia during the sacrifice, and thus she was saved by the goddess according to tradition. The Sacrifice of Iphigenia has been transmitted to us by a Roman mosaic found in Ampurias and by a painting of the Museum of Naples, both interpretations may retain some of Timanthes’ painting.

The painter Apelles belonged to another generation. His fame made Alexander to grant him the privilege to paint his portraits. Among his most famous paintings was an Aphrodite Anadyomene or Venus rising from the sea which came to be for painting what the Venus of Knidos was for sculpture.

There are also several written references to other paintings of Apelles representing Alexander in conversation with the gods or totally deified. To Apelles, or to his disciple Filoxenos, was attributed the original of a mosaic from Pompeii which can be admired now in the Museum of Naples. Depicts the Battle of Issus, where Alexander personally attacked the group of 1,000 spearmen called the immortals who formed the invincible escort of the Persian King Darius. The Macedonian hero with his disorganized hair charges on horse to fight the feared Persian warriors and leads confusion to the same chariot of Darius. The famous battle was skillfully summarized in this episode in a single scene where all Alexander’s glory and the Greek victory were expressed. There is no indication of the place other than a rare tree trunk, but the depth of the space is skillfully suggested by the different inclination of the spears which intersect each other indicating space between the combatants.

Another painter of the era was Ethion. A painting presumably by Ethion is one fresco discovered in Ostia which is now in the Vatican Library. In the center there is the beautiful group of the wife with pale face and wearing a veil while listening to the latest advice of a seminude Venus. The husband, crowned with flowers, waits impatiently at the side of the bed while on each side of the room the women prepare the water or chant hymns.

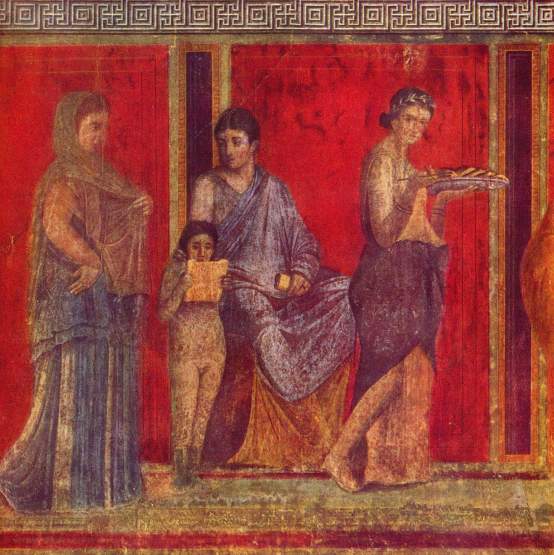

From the same style of the IV century BCE, or at most from the early III century BCE, was the model of a large composition discovered in a suburban villa of Pompeii called the Villa of the Mysteries. They are until today the most beautiful frescoes recovered from antiquity, the only of large dimensions with numerous figures larger than natural. The subjects depicted are extremely interesting: on one side there is a painting representing a mother which teaches reading to a child and is visited by her friends, probably with the aim of going to an initiation party for a new kind of “mysteries”. Below there is a big area with curious representations of the ceremonies: several young women are possessed by frenzy or Bacchic delirium befitting a strange ritual, they are being pursued by some black and winged figures, and are performing a dance completely naked, one of these girls falls stunned on the knees of her companion that tries to revive her.

_______________________________

Allegory: In art refers to the description of a subject in the guise of another subject. An allegorical painting might include figures emblematic of different emotional states of mind – for example envy or love – or personifying other abstract concepts, such as sight, glory, beauty, Revolution, or France. These are called allegorical figures. The interpretation of an allegory therefore depends first on the identification of such figures, but even then the meaning can remain elusive.

Allegory: In art refers to the description of a subject in the guise of another subject. An allegorical painting might include figures emblematic of different emotional states of mind – for example envy or love – or personifying other abstract concepts, such as sight, glory, beauty, Revolution, or France. These are called allegorical figures. The interpretation of an allegory therefore depends first on the identification of such figures, but even then the meaning can remain elusive.

Contrapposto: An Italian term that means counterpoise. It is used in the visual arts to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs. This gives the figure a more dynamic, or alternatively relaxed appearance. The leg that carries the weight of the body is known as the engaged leg, the relaxed leg is known as the free leg. Contrapposto was an extremely important sculptural development, for its appearance marks the first time in Western art that the human body is used to express a psychological disposition.

Contrapposto: An Italian term that means counterpoise. It is used in the visual arts to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs. This gives the figure a more dynamic, or alternatively relaxed appearance. The leg that carries the weight of the body is known as the engaged leg, the relaxed leg is known as the free leg. Contrapposto was an extremely important sculptural development, for its appearance marks the first time in Western art that the human body is used to express a psychological disposition.

Forum: (from the Latin forum meaning “public place outdoors”, pl. fora). A public square in a Roman municipium, or any civitas, reserved primarily for the vending of goods; i.e., a marketplace, along with the buildings used for shops and the stoas used for open stalls. Many fora were constructed at remote locations along a road by the magistrate responsible for the road, in which case the forum was the only settlement at the site and had its own name.

Forum: (from the Latin forum meaning “public place outdoors”, pl. fora). A public square in a Roman municipium, or any civitas, reserved primarily for the vending of goods; i.e., a marketplace, along with the buildings used for shops and the stoas used for open stalls. Many fora were constructed at remote locations along a road by the magistrate responsible for the road, in which case the forum was the only settlement at the site and had its own name.

Tholos: (from Ancient Greek, pl. tholoi). An architectural feature that was widely used in the classical world. It is a round structure, usually built upon a couple of steps (a podium), with a ring of columns supporting a domed roof.

Tholos: (from Ancient Greek, pl. tholoi). An architectural feature that was widely used in the classical world. It is a round structure, usually built upon a couple of steps (a podium), with a ring of columns supporting a domed roof.