In Wittenberg, Cranach’s style underwent further change and so radical that, for a long time, the works he made in Vienna weren’t attributed to him by scholars. That change was visible by the development of a style that would become specific to Cranach and his school: decorative, pictorial, ample, smooth, courtly, and mannerist. Along with religious themes, he also painted profane themes: genre paintings, mythological scenes and, above all, portraits, generally half-length figures on a neutral background.

Traces of Cranach’s future artistic trend appeared in the woodcut Four Saints Adoring Christ crucified on the Sacred Heart (1505), made in Wittenberg and based on an ancient allegorical theme related to Christ’s love for humanity. Its composition shows a symmetrical balance, with defined contours, far from any idyllic environment. What this engraving already announced became effective to a high degree in Cranach’s pictorial work of coming years.

An early example is the Triptych with the Martyrdom of St. Catherine, painted in 1506 (Dresden). In its central panel, we see the saint on her knees, praying submissively, with her gaze raised to heaven, sumptuously dressed in fashion and surrounded by a crowd whose layout and structure is confusing and problematic. Two figures stand out from the group: the executioner, tall and upright, who wields the sword to carry out the sentence, and the page on the far left of the central panel, dressed with elaborate elegance and whose face expresses indifference. The landscape doesn’t complement the composition: the will to unite characters and landscape and the overwhelming impulse of his youthful works here are lacking. The central panel of the altarpiece denotes that it was made in a troubled time for Cranach. The panels of the side-wings represents each a group of three female saints.

In the Triptych with the Holy Kinship, from Torgau, painted in 1509 (Frankfurt) and in the Princes’ Altarpiece (ca. 1510; Dessau) Cranach achieved a more serene and classical composition distributed with greater clarity in the pictorial space. The relationship of the characters to each other now corresponds to the exterior background. In addition, there are clearly individualized traits in the characters and the theme is presented with great wealth of detail.

Undoubtedly, the works of this period are marked by the knowledge Cranach obtained during his trip to the Netherlands in 1508. Prince Elector Frederick the Wise sent his chamber painter to the camp of Emperor Maximilian, who was then in Mechelen (currently in Belgium).

By this time, the sense of space, the balance of the composition, the treatment of color, and the command of the line demonstrate Cranach’s knowledge of Dutch and Italian painting. Numerous wood engravings came from that time, such as the Santoral of Wittenberg, with 117 woodcuts, and the Passion Series, with 14 engravings, begun in the same year that Dürer began his “Little Passion”. However, Cranach’s Passion used a totally independent exposition of the Biblical texts and employed colored engravings as well as his first copper engravings. If one considers that, in addition to his activity as a painter and copper engraver, Cranach also made sketches for wood engravings, for paintings on glass and for tapestries, hangings and weapons, one can easily understand the admiration of his contemporaries for the speed with which he was able to work.

In any case, Cranach owned a large workshop including up to ten assistants, in addition to his sons Juan, who died prematurely in Bologna in 1537, and Lucas, who later took over his father’s workshop. Many themes were repeated in this workshop in different variants (for example, there are more than 30 paintings on the themes of Lucrecia, Venus and Eva).

Lucretia, from 1510-1513, is one of the earliest paintings on the classical subject by Lucas Cranach the Elder. According to Roman tradition, Lucretia (a noblewoman in ancient Rome) was raped by Tarquin (one of the sons of the last king of Rome) and as a consequence committed suicide by stabbing her heart. This fact precipitated a rebellion that ultimately led to the overthrew of the Roman monarchy and to the transition of Rome from a kingdom to a republic. This depiction of Lucretia by Cranach is the most sensual that he produced. His fascination with the story of Lucretia is reflected in the numerous paintings on the subject that he executed, around 35 versions attributed to him or his workshop.

The delicate Venus from 1529 (Paris) corresponds to the prototype of feminine beauty created by Lucas Cranach the Elder based on Gothic types. We find here the adolescent figure, almost a girl, whose graceful body, with small breasts and a long neck, is provocatively adorned with a necklace and a luxurious, ostentatious hat. Her slanted eyes, malicious, seem to know very well that her veil, more than veiling her nudity, highlights it. To better emphasize the ivory whiteness of her body, Cranach has placed her silhouetted against a somber background of foliage. Contrary to the landscape in the background, Cranach didn’t seek any realism in the figure of Venus, but rather an accentuated mannerism that is accentuated in her pose, and that transmits an exciting sophistication. The landscape conveys in a few strokes an intense impression of the Germanic conception of nature. This painting of Venus is just one of a series of paintings in various sizes, representing Venus or a female nude, turned out in quantities by Cranach and his studio; the same subject that were popular among the clientele of humanists for whom he worked.

The various paintings with the theme of Adam and Eve (this shown here ca. 1510, Warsaw) painted by Cranach and his workshop revealed with no doubt the influence of Dürer and the models he provided with his engraving of 1504 and the two life-size panels from 1507 on the same subject.

After his trip to the Netherlands, themes from Antiquity, historical themes and typical genre scenes acquired a certain importance in Cranach’s work. The cultured and humanist atmosphere of the court favored the creation of compositions that evoked moral concepts as well as representations of the naked human body. At that time the theme of “Venus and Love” was highly appreciated, “while the child Cupid steals the honey from the hive, a bee sticks its sting into the finger of the little thief; so too, we often eagerly seek fleeting pleasures that are mixed with pain and will only bring us harm” this statement frequently read as the justifying legend that accompanied the figure of certain extremely slender and refined female nudes by Cranach (Venus and Cupid, 1509, St. Petersburg; Venus and Cupid with a Honeycomb, ca. 1525, Rome). The Venus and Cupid from 1509 is the earliest of his mythological paintings and the first in Germany depicting a naked Venus and Cupid. The painting includes a moralizing Latin couplet that reads: “Reject Cupid’s lasciviousness with all your might, or else Venus will possess your blinded soul.” The composition of the painting was strongly influenced by Dürer. In Venus and Cupid with a Honeycomb, from ca. 1525, Venus is shown draped in a transparent veil while gazing directly at the spectator. The fine brushwork captures every wrinkle in the bark of the tree at the left and every feather in Cupid’s wings. Again, Cranach accompanied his nude with a moralizing couplet by the Humanist Chelidonius which tells us that ‘voluptas‘ is transitory and accompanied by pain, as the little Cupid realizes when he tastes the honeycomb with its stinging bees.

Through the observation of these paintings we see that the boundaries between religious and secular themes were then blurred; Cranach’s religious themes tend to look similar to those of antiquity. In this way, in the painting St. Mary Magdalen, painted in 1525 (Cologne), there is an absolute contrast between the courtly clothing, the affectation of the gesture, the idyllic landscape in the background, and the subject itself. St. Mary Magdalen’s rich costume and her affected gesture make her similar to a card figure that blends perfectly into the landscape, a lyrical counterpoint in which the religious is gently diluted into the profane.

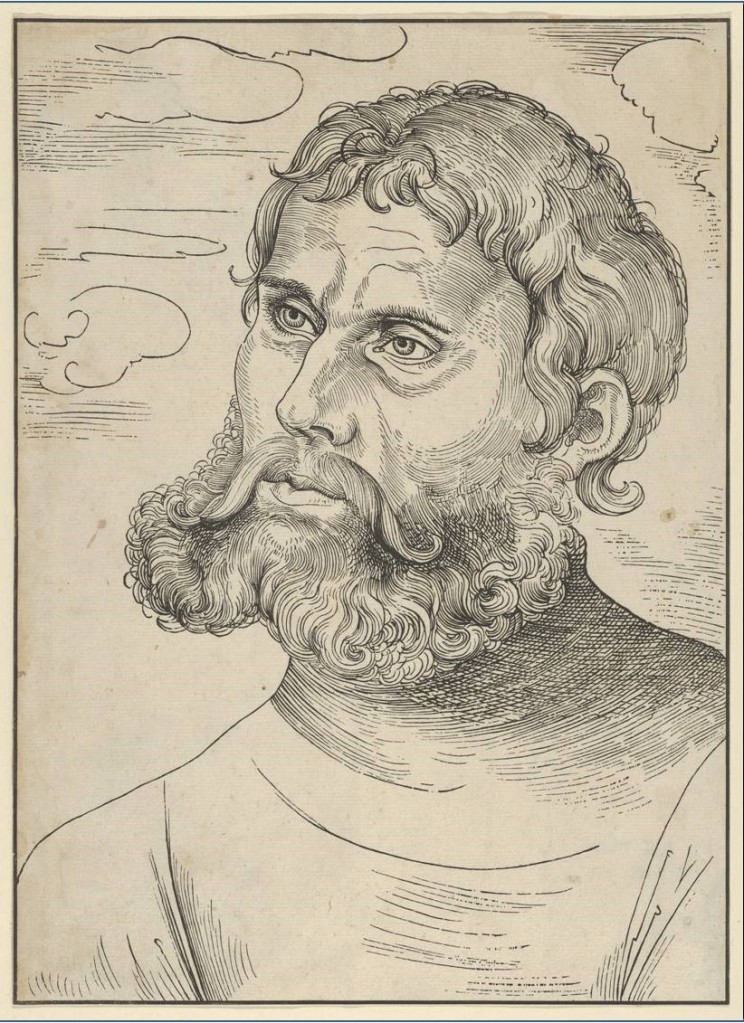

Lucas Cranach wasn’t content with his privileged position at the court of Wittenberg, where he was linked by a personal friendship with the family of the Elector, nor with his qualities as a notable representative of his fellow citizens, with whom he collaborated in decisions about the city as Council member and burgomaster. Cranach also took part in the struggles of the Reformation. He was a great friend of Martin Luther and he painted the portraits of the reformer for his contemporaries. Luther had been godfather of Anna, Cranach’s daughter; the painter, in turn, asked, in behalf of his friend, for the hand of Luther’s future wife, Katharina von Bora, and was best man at their wedding ceremony. In 1526, Cranach offered himself as godfather to Luther’s first son. In 1520 he had already engraved on copper the first portrait of Luther, in a monk’s habit; in 1521 he made a second engraving of Luther, seen in profile, wearing the cap that identified him as doctor of philosophy; a short time later, a wood engraving, known as Luther as Junker Jörg, his disguise as a knight during his exile in Wartburg castle between May 4, 1521 and March 1, 1522.

Cranach’s workshop produced the illustrations for Martin Luther’s New Testament Translation first printed in September 1522. Consequently, with the help of a Council member, Cranach himself set up its sale and subsequent editions. Although loosely based on the illustrations for the Apocalypse by Albrecht Dürer, Cranach’s 21 compositions aimed to interpret the Revelation of St. John as closely as possible to the text. As a consequence, Cranach’s renditions of the Apocalyptic scenes are straightforward and lack unnecessary embellishment following tightly with the conceptions of Martin Luther who considered that art should clarify the meaning to benefit the illiterate. In this sense, we can think that Cranach’s ultimate goal with this accompanying illustrations was to improve upon existing imagery as well as to the clarity of the storyline. We can notice this more literal interpretation of the biblical scenes than those designed by Dürer, by observing Cranach’s rendering of the Vision of the Seven Candlesticks: “and out of his mouth went a sharp two-edged sword: and his countenance was as the sun shineth in his strength. And when I saw him, I fell at his feet as dead” (Revelation 1:16-17). In some other illustrations, like The whore of Babylon (Revelation 17–18), we can also notice a clear Protestant agenda: Cranach emphasized the harlot’s identification with the alleged corruption of the Catholic Church by placing the triple tiara of the papacy upon her head.

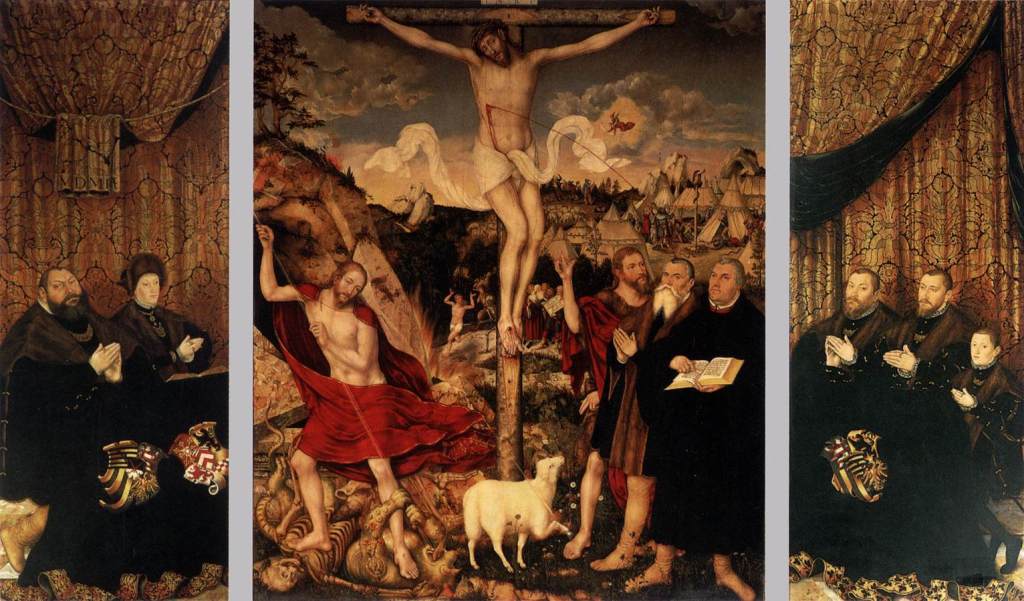

In close collaboration with Luther and Melanchthon (both protestant reformers), Cranach painted a series of altarpieces in the spirit of the Reformation: the one in the Dessau castle church (known as Princes’ Altarpiece), the one in the main church of Weimar (completed by his son Lucas Cranach the Younger) and that of the main church of Wittenberg (known as the Reformation Altar).

The Altarpiece of Wittenberg’s main church was consecrated in 1547; it consisted of eight paintings forming two groups of four panels: a large central panel, two lateral panels (painted probably by Lucas Cranach the Younger), and a predella. The thematic composition of the altarpiece was based on a program closely related to the new ecclesial reforms: baptism as admission into the community, communion as a realization of the union with Christ, and confession as preparation for the sacrament of the Eucharist. The predella represents the preaching of the Gospel, with the Crucifixion in the center, on the left the community, and on the right Luther from the pulpit, pointing with his right hand to the Crucified. This image was a total novelty compared to the traditional images depicted on predellas up to that time. The Reformers, still alive at the time, were included in this pictorial account: Melanchthon baptizes a child, Bugenhagen is confessing under the symbol of the key, Luther preaches from the pulpit.

Cranach displayed the same background for the two wings and for the predella: a stone wall. Only the central panel representing communion has a landscape background; the arrangement of the sacrament ceremony, within a closed oval, opens only in the scene of the pourer, a special reference to the chalice and communion since the apostle who is being served by the man in red who fills the chalice has the features of Luther as Junker Jörg. The reverse of the panel complement the front scene with the vision of the Church as a community.

Cranach’s altarpieces from the Reformation period should not be interpreted solely from an aesthetic point of view, but taking into account the new Reformation interpretation of the themes of Sacred History.

Cranach achieved great renown with his portraits. Those of the Viennese period were already capital works of German painting; those of his last period demonstrate his view of the human character. In addition to the many official and courtly portraits, such as that of Frederick the Wise, that of Henry the Pious, Duke of Saxony and his wife Katharina von Mecklenburg, from 1514 (Dresden), that of the young Portrait of a Saxon Prince, from 1517 (Washington D.C.), the portraits of the bourgeoisie, such as that of Luther’s parents Margaretha and Hans Luther, from 1527 (Eisenach), all achieved a greater impact. We know several studies of Cranach’s portraits, mostly colored brush drawings. These sketches show that Cranach, unlike Dürer, did not consider his drawings as finished and complete works.

Cranach’s fate was closely tied to the political events of his time and his position as a chamber painter. In the battle of Mühlberg (1547), the Elector Frederick of Saxony fell prisoner of catholic Charles V of Spain. Charles V had Lucas Cranach come to his camp and discussed with the painter one of his pictures, asking him the question, quite significant, whether he or his son was the author, in the midst of the conversation Cranach requested clemency for his prince. In 1550, Cranach accompanied John Frederick of Saxony to his captivity in Augsburg, having made a will and resigned to his official appointments. In Augsburg he met Titian, who was doing the famous equestrian portrait of Charles V. In 1551 Cranach followed the prince to Innsbruck, and when John Frederick was restored as duke in 1552, the artist returned with him to Weimar, to the elector’s new residence. At the age of 82, he was again named chamber painter, but he died on October 16, 1553 in Weimar.

From 1537, the symbol of the serpent with vertical wings included in Cranach’s coat of arms was modified and the wings appeared horizontal. It can be concluded that Lucas Cranach the Younger, who was helping his father more and more in the workshop, took it entirely under his responsibility starting in 1550, when his father followed the prince into exile in Augsburg and Innsbruck. Cranach’s son continued to work in the style of his father and probably achieved his greatest perfection in his portraits, which were generally simple in arrangement, but often empty in mannerisms that gave the characters a certain puppet-like appearance. The importance of the Cranach workshop continued in Saxony until the death of Cranach the Younger in 1586.