To study the Romanesque Art we’ll begin with the study of the French Romanesque schools, because contrary to the Spanish Romanesque schools, they were not in contact with an exotic element like the Muslim art, neither they had a haunting vision of the classical Roman monuments like the Italian Romanesque schools did.

Of all French Romanesque schools, the one that most kept the Roman classical forms was that of Provence. Chronologically, Provençal Romanesque churches aren’t the oldest works of French Romanesque architecture, but for their style they are consider the most Romanesque in the sense that they were the closest to Roman artistic traditions. These Provençal Romanesque churches were built with large stones and their lateral naves (covered with quarter circle vaults) functioned as buttresses to the central nave (covered with barrel vaults). Over the crossing they generally had towers or domes with two floors from where light came into the church, which allowed them to have a great medieval appearance, though outside they appeared almost Roman. The exterior of these Provençal Romanesque churches wasn’t austere: they had facades with smaller columns, similar in proportion and appearance to Corinthian columns, and had friezes imitating ancient Christian sarcophagi. The main churches of this Provençal group are those of Carpentras, Nimes, Cavaillon, St. Trophime in Arles, Saint-Gilles-du-Gard and the Avignon Cathedral. The churches of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard and St. Trophime in Arles are the most famous, especially for their facades, although inside they are of great simplicity and almost without sculptures.

Another French Romanesque school was the school of Languedoc. Its best example is the great collegiate church of Toulouse, dedicated to its patron Saint Sernin. This is a magnificent five-nave basilica with crossing and ambulatory (the result of one of the lateral naves running behind the main altar and with some adjacent chapels). The arrangement of the ambulatory is essentially French and was typical of churches located in the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela, in next essays we will see how the Rhine Romanesque cathedrals didn’t have this element. The church of St. Sernin, from 1080, is considered the masterpiece of the French Romanesque architecture, precisely because of the structure of its apse with ambulatory and chapels. Another “pilgrimage church” with ambulatory is the elegant church of Sainte-Foy, from mid-11th century, located near the medieval village of Conques. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Languedoc was the brightest center of Western culture, and it is understood that it took advantage of the most advanced methods of architecture known at the time; hence, Romanesque architectural forms appeared more advanced in Languedoc than in Provence. These two cultures, the Provençal and the Languedoc, ended colliding with each other and finally, under the excuse of fighting the alleged Albigensian heresy, the Provençal culture disappeared. After the destruction of the county of Toulouse (in Provence), most Provençal artists emigrated, which helped to extend the influence of this southern French art school throughout Italy and Spain. This parallels what happened with Provençal poets and troubadours who took refuge in the courts of Castile and Aragon and in Italy, something similar to what happened in the arts.

Other of the French Romanesque schools was that of Auvergne in Central France, exemplified by the Cathedrals of Puy and Notre-Dame la Grande in Poitiers. Architecturally, Auvergne is often regarded as the first center of Romanesque art. In Central France, churches always had ambulatories and their lateral naves had two floors: a lower one, covered by groin vaults, and an upper one, covered with quarter circle vaults forming the upper galleries. In this way, the highest part of the central nave received indirect light coming into the church through the upper gallery, while the lower part of the central nave received the light coming from the lateral naves. The most representative example of this school of Auvergne is the church of Notre-Dame-du-Port in Clermont-Ferrand. Auvergne churches were poorly decorated compared with those of Provence. On the outside, Auvergne Romanesque buildings were decorated with large arches applied directly to the walls, and architects used stones of different colors as it was done during the Carolingian period. Sometimes the church’s facade was flanked by tall structures, like in the cathedral of Puy, or by towers topped with conic domes in the shape of miters. Such domes are also present in the cathedral of Angoulême and in Notre-Dame la Grande in Poitiers. The cathedral of Angoulême has those same decorative arches on the facade like in the cathedral of Puy, only that instead of being a simple, natural polychrome decoration, here it is full of sculptures arranged inside the arches as if they were inside niches. This same system was adopted to decorate the elegant facade of Notre-Dame la Grande in Poitiers in 1143, which survives almost intact to this day.

In the regions of Aquitaine and Perigord domes were appearing more frequently as if they were to replace the barrel vaults. The Angoulême Cathedral has hemispherical domes covering its central nave. These domes appear also as main structural element in Cahors, Solignac, and the great abbey of Fontevrault, from the early 12th century, with large domes over its main nave. But the most famous example of Romanesque domes is the church of Saint-Front de Périgueux (1120-1150), with five large domes on squinches resting on square pillars defining a Greek cross floor plan that seems to repeat with Romanesque features the Byzantine cathedral of Saint Mark in Venice, which in turn followed the ancient model of the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. These domes of Saint-Front de Périgueux were the models for several other buildings, and even in modern times they have been imitated in cathedrals such as the Basilica of the Sacred Heart (Sacré-Cœur) in Montmartre, and the church of Our Lady of Fourbiéres, near Lyon, both with domes like those of Saint-Front.

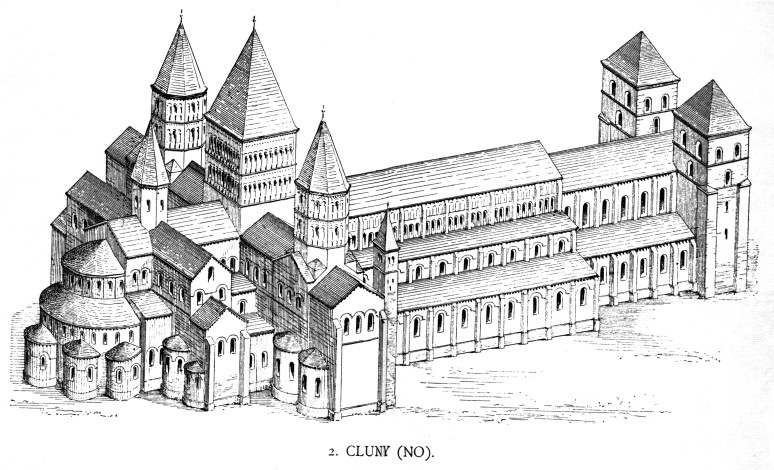

A school that later gave origin to the Benedictine Cluniac art was that of Burgundy. The Burgundian builders eagerly used groin vaults with diagonal arches, called groins*. These vaults will later become the characteristic vaults of the Middle Ages. The architects of Burgundy initially arranged groin vaults on a church’s lateral nave without using groins in the same way Romans did before; later, they traced these vaults over the central nave, and progressively projected these vaults in increasingly wider spaces, a situation that required the use of these diagonal arches (or groins). The most emblematic construction of the Burgundy school was the third church of the Abbey of Cluny, with five naves, built between 1088-1131 and that was for a long time the largest church in all Christendom. This church was a model that influenced many other large churches such as the cathedral of Autun and the Abbey of Vezelay from 1120. We have to study these last monuments to imagine how the basilica of Cluny looked like, since it was destroyed during the French Revolution. The Art of Cluny, its influence and consequent expansion across Europe will be discussed in other essay.

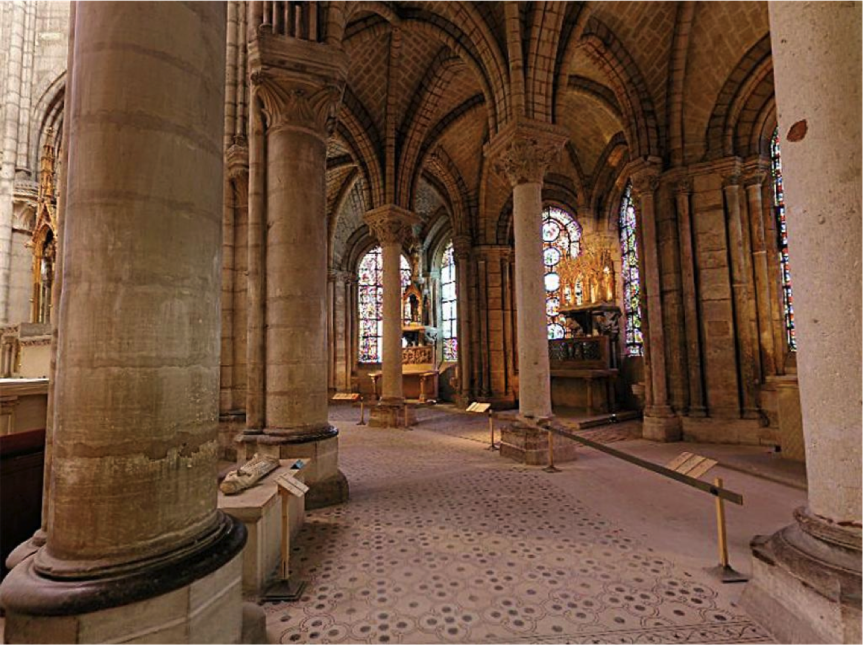

The fifth French Romanesque school was the Royal Domain located in areas around Paris called Ile de France. There is the old church-pantheon of Saint-Denis, founded by Dagoberto, rebuilt in the eighth century, and finally newly rebuilt by Abbot Suger to be consecrated in 1140. Saint-Denis is unique in its geometry and introduction of a beautiful innovation: the circle of chapels of the ambulatory, which makes the interior of the church to be permanently bathed in a wonderful light that gradually spreads from the big windows along the whole construction filling the whole temple with light. More than the last example of the Romanesque style, Saint-Denis is considered the first truly Gothic cathedral. However, in this region the monument that exhibits the most pure Romanesque style is the monastery of Fleury in Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire. This temple has a famous porch-tower, a huge transept located almost at the center, and an ambulatory with chapels.

The School of Normandy, originated in Northern France, was influenced by Normans who came to invade England in the 11th century. Norman churches were high, harmonious, well arranged, and had plenty of light. The climate in Northern France required the central nave to be higher than the laterals. Initially, the central nave was covered with a wooden ceiling, because the thrust exerted by a barrel vault could not possibly be counteracted in a nave so high. Later, when architects were familiar with groin vaults, the naves were modified and wooden ceilings were replaced with stone vaults. This is what happened in two large churches in Caen (Saint-Étienne and The Trinité), both built in the second half of the 11th century and covered with groin vaults. Norman style decoration was very characteristic: it had almost no sculptures, but lots of geometric ornaments, a reminiscent of the Nordic style. The facades of the churches of Caen have three doors corresponding to their three naves, and are flanked by two tall and powerful towers with buttresses. This same disposition was copied by Abbot Suger in 1137 when he began working in Saint-Denis, the first Gothic church. Norman decorative motifs were also present in British monuments from the XII century and in buildings constructed by Normans in other countries farthest from France.

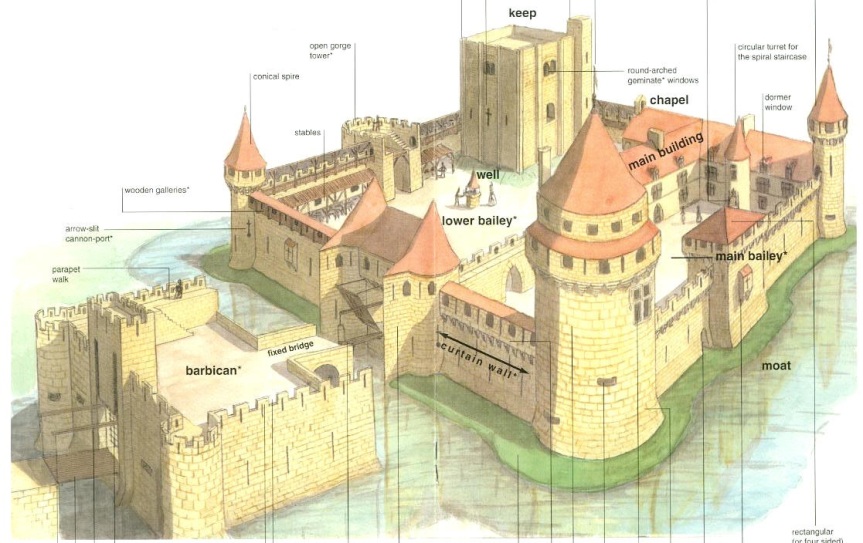

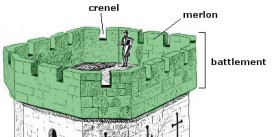

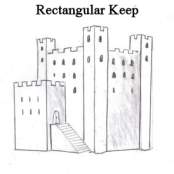

In France there are numerous castles that still have remains of the primitive Romanesque fortresses. The feudal castles from this period had usually a robust tower or keep* (donjon), where the feudal lord lived with his family and servitude. This tower had two or three floors with a spacious room on each one: the bottom floor was used as a warehouse for weapons, utensils and food; on the main floor was the living room, which served as dining room or even as a dormitory; the upper parts were destined to the servitude. Sometimes this big tower was attached to a smaller tower which enclosed a ladder, and these both were separated from the rest of the fortress by an interior moat*. Surrounding the tower it was the area with the farms for the servants’ families and barns for cattle, these in turn were protected by a second moat and a wall. In the most important castles, the outer wall was interrupted by regularly spaced towers with battlements or merlons* joined together by a walkway.

The castle of Foix, on top of a rock overlooking the city of the same name, has this features. But in the south of France the largest of these fortified precincts is located in the Cité de Carcassonne, even though part of its walls are from the Visigoth period and others have been highly restored. Inside, it has many ancient constructions and whole streets forming a medieval complex with its arcades, squares and churches.

The most important civil monuments in Romanesque France were bridges. These bridges were almost always kind of narrow and, if necessary, only had one arch. As a consequence, they were built resting on rocks on either side of the river. However, over large rivers, there were bridges with several sections. At this time, the most famous bridge in France was that of Avignon over the Rhone river, imitating the structure of an ancient Roman bridge. Other example is the bridge of Bonpas, also in Provence, over the Durance river.

______________________________________

*Battlement: In a fortified structure a battlement refers to a parapet or defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which rectangular gaps or indentations occur at intervals to allow for the discharge of arrows or other missiles from within the defences. These gaps are termed “crenels”. The solid widths between the crenels are called merlons. Battlements on walls have protected walkways behind them.

*Battlement: In a fortified structure a battlement refers to a parapet or defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which rectangular gaps or indentations occur at intervals to allow for the discharge of arrows or other missiles from within the defences. These gaps are termed “crenels”. The solid widths between the crenels are called merlons. Battlements on walls have protected walkways behind them.

*Groin: A curved edge formed by two intersecting vaults.

*Groin: A curved edge formed by two intersecting vaults.

*Keep: A type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages. Usually they refer to large towers in these castles that were fortified residences, used as a refuge of last resort if the rest of the castle fall to an adversary.

*Keep: A type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages. Usually they refer to large towers in these castles that were fortified residences, used as a refuge of last resort if the rest of the castle fall to an adversary.

*Moat: A deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that surrounds a castle, fortification, building or town, to provide it with a preliminary line of defense.

*Moat: A deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that surrounds a castle, fortification, building or town, to provide it with a preliminary line of defense.