At the beginning of the 16th century, a new national consciousness was achieved in Germany, especially among humanists; its goal was the realization of the traditional concept of Empire: the unity of the Empire and the Emperor. In Nuremberg also arose the notion of a new citizen’s dignity. Luther said of Nuremberg that it was “the eyes and ears of Germany” and Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II) called it “the center of the Empire”. Since 1424 the city had housed the imperial insignia: the crown, the scepter and the sword —signs of earthly power— and, along them, the relics of the Empire, which were kept in the church of the Hospital of the Holy Ghost (the Heilig-Geist-Spital). The city entrusted Dürer with the decoration of the two large panels that were hung on either side of the shrine in which the relics and imperial jewels were housed. For the composition of these two large panels (Nuremberg), Dürer produced several study cartoons. One panel shows Emperor Charlemagne, the legendary founder of the Holy Roman Empire; in the other, the Emperor Sigismund, of the house of Luxembourg, who had had the jewels brought to the city. For the latter’s features, Dürer followed a 15th-century portrait; for those corresponding to the Emperor Charlemagne he adopted those by Johannes Stabius, a court chronicler, who in 1512 resided in the city. This commission from the year 1510 was the only one that his hometown made to the painter.

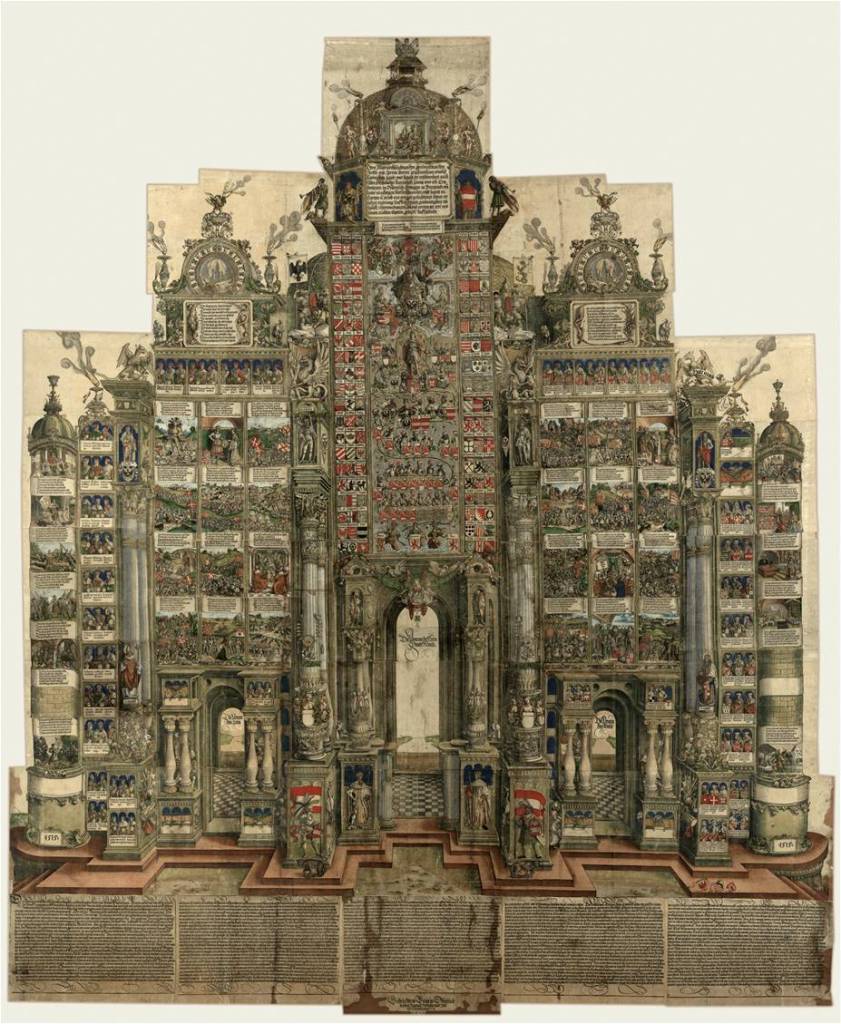

The presence in Nuremberg of Emperor Maximilian (starting in 1512), placed Dürer in a preferential position for imperial commissions. The emperor found in Dürer the artist capable of understanding and interpreting his ambitious projects for the historiographical and genealogical chronicle that he was envisioning and in which he wanted to transmit to posterity his glory and that of his lineage. Of the many artists who worked for him, Dürer was the only one who received a life pension. Dürer and his workshop also collaborated on the monumental Triumphal Arch for Emperor Maximilian, produced in 1515. This arch was more than three meters high and was made up of 192 wooden carvings that, joined together, formed a Roman-style triumphal arch. The monumental composition narrated the exploits of Maximilian and gave details about his genealogy.

The Great Triumphal Chariot was conceived in the same way, Dürer only made the chariot. Simultaneously, Dürer and his workshop worked on illustrating the emperor’s books with wood engravings: Weisskunig, Freydal, Teuerdank, are all autobiographical novels. These set of illustrations for the emperor’s breviary is one of the most beautiful ever made. In addition to Dürer (who with his 50 sheets outnumbered the other participant artists and determined, formally and in style, the body of the work) collaborated in these illustrations: Lucas Cranach the Elder, Hans Baldung Grien, Hans Burgkmair, Jörg Breu the Elder and Albrecht Altdorfer. The illustrations that accompany the texts are made up of pen drawings on parchment, full of fantasy and color (red, green, violet), their decorative ornamentation is mixed with fabulous beings, combining the grotesque with the sacred.

Dürer worked on three portraits of the emperor: the first was a charcoal drawing made in Augsburg on June 28, 1518 (Vienna). Closely similar to this drawing are two paintings (Vienna, Nuremberg) and a wood engraving on the same subject that Dürer made after Maximilian’s death in 1519 (London).

The xylography with the emperor’s portrait would be the first of the series of engraved portraits that had the purpose of communicating the features of the sitter. Thus, the copper engravings of Cardinal Albert of Brandenburg (1519 and 1523), of Prince Frederick the Wise of Saxony (1524), of Willibald Pirckheimer (1524), of Philippe Melanchthon (1526), of Erasmus of Rotterdam (1526) and Ulrich Varnbühler‘s wood engraving (1522). With these, the portrait was definitively freed from its former dependence on religious themes, to which it was still attached.

The painted portrait, as an autonomous genre, did not appear until the end of the Middle Ages, and in Germany until well into the second half of the 15th century, when a new citizen consciousness emerged: that of the bourgeoisie. Often the portrait was combined in movable diptychs, with the image of the sitter on one side and the image of the Virgin or the head of Christ crowned with thorns on the other. The new awareness of the value of personality developed during the Renaissance and created its own forms of expression. The preferred type of individual portrait was generally of half-length, with hands visible, almost in profile, and against a neutral background. Exceptions were frontal representation or absolute profile. Dürer actively participated in perfecting the pictorial portrait. He was of the opinion that the appearance and physicality of people should be able to be transmitted after death. For this reason, in the whole of Dürer’s work, the portrait occupies a place of equal importance to other pictorial subjects. In the evolution of the portrait he came to the conclusion that the physiognomic characteristics of the sitter were not enough, but that the portrait had to reproduce at its best the whole of the sitter’s personality, which makes each person unique and particular.

Throughout Dürer’s work one can continually find his special interest in portraiture. This is visible in the portraits of his father, from 1490 (Florence) and 1497 (London), the former a pendant with one portrait of his mother (1490, Nuremberg); in that of the Elector Frederick the Wise, 1496 (Berlin); and in that of Oswolt Krel, from 1499 (Munich). In these early portraits, Dürer pursued above all a plastic conception of the figure, without always penetrating the psychological complexity of the individual.

In 1498 he painted his second self-portrait in oil, where, before an alpine landscape, he presented himself confident and with elegant clothing (Madrid), and on the panel painted in 1500 he represented himself in an absolute frontal position, prerogative until then granted only to the face of Christ, with an exact and idealized symmetry (Munich), totally confident and aware of himself. At the time, the Germans still considered the artist as a craftsman, as had been the conventional view during the Middle Ages. Dürer was not totally contempt with this view, as we can see in this two self-portraits showing him almost as an aristocrat, a proud and pompous young man. By showing off his stylish and expensive costumes, Dürer wanted to let us, his viewers, know that he considered himself no mere limited provincial. Whit his confident self-portraits, Dürer insisted mostly in his dignity. His Self-portrait in the nude (Weimar) also represents a bold statement about himself, it is considered the first nude self-portrait by an artist. Though he wears a hairnet, his body is represented with absolute naturalism and merciless, his skin is even drooping in different places.

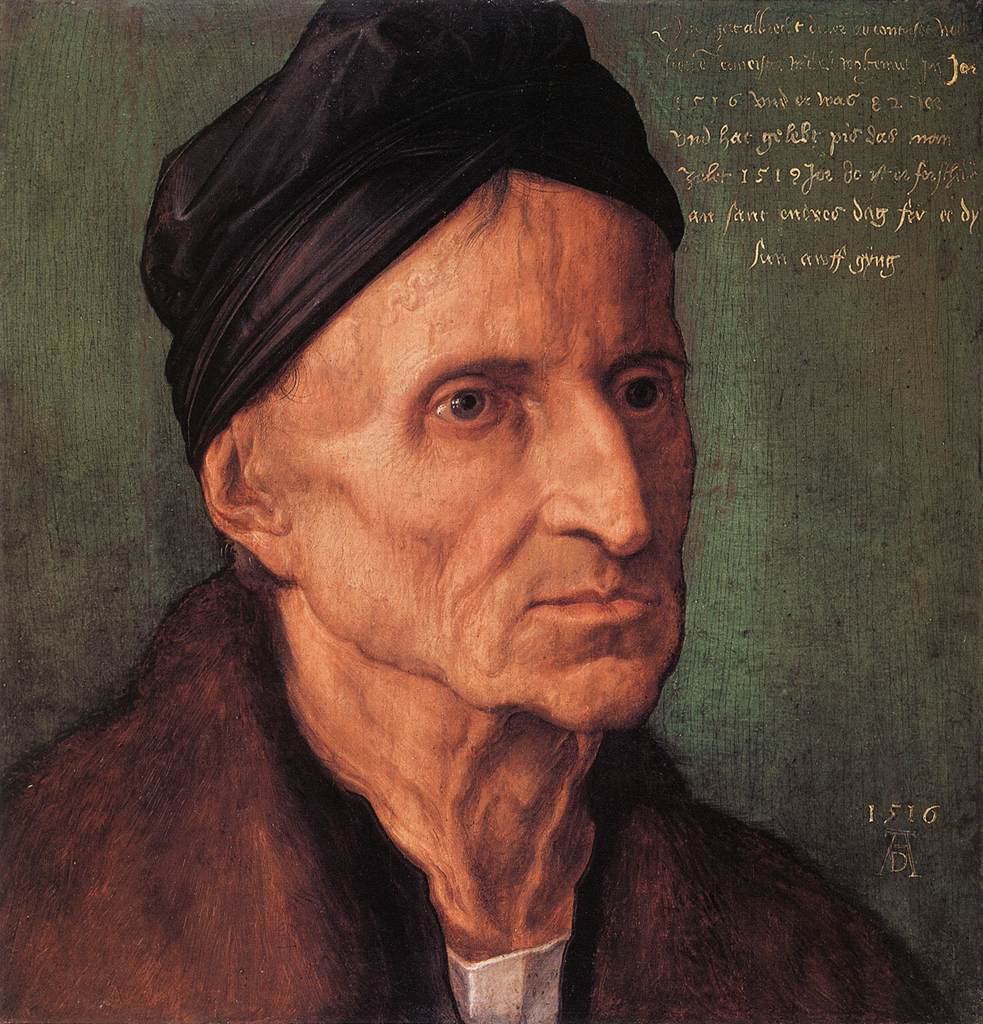

After his second stay in Venice (1505-1507) and under the influence of contemporary Venetian painting, Dürer achieved a convincing individual interpretation of the sitter, like in the unfinished portrait of the Young Venetian Woman (Vienna). But it is in the portrait of his revered and by then old teacher, Michael Wolgemut (1516, Nuremberg), where his disciple manifested his personal understanding of the individual characteristics of the subject. With bold strokes, Dürer has given us the strong features of the old man, giving more importance to the pictorial nuance than to the plastic-linear features of the portrait. In this bony face stand out the wrinkles, sunken cheeks, nose’s prominent curve, and blue and transparent eyes of the then 82-year-old man, all described with maximum intensity. The portrait depicts him endowed with great inner strength and deep gravity.

With his trip to the Netherlands, from 1520 to 1521, Dürer began the series of grandiose portraits of his mature period: for example, the portrait of Bernhard von Reesen, from 1521 (Dresden); the Portrait of of a Man with Beret and Scroll, from 1521 (Madrid); those of Hieronymus Holzschuher and Jakob Muffel, both from 1526 (Berlin); and that of Johann Kleberger, from 1526 (Vienna). These portraits are capital works of Dürer, as well as of old German painting. Later, when he has already reached the last stage of his life, he returned to the clear and purely plastic forms of his first epoch.

During Dürer’s time, German humanism developed through the rediscovery of ancient culture, the study of theology, and a new national awareness. His friend Willibald Pirckheimer was the most learned secular humanist of his day, and he certainly advised and influenced the artist. Was Pirckheimer who encouraged Dürer to include in his religious subjects a special humanistic nuance of Christian nature, like in his copper engravings Adam and Eve and Nemesis. The first is the expression of the beauty of the first human couple, the harmony of the human race with Nature; the second presents a vision of the world according to the canons of Antiquity.

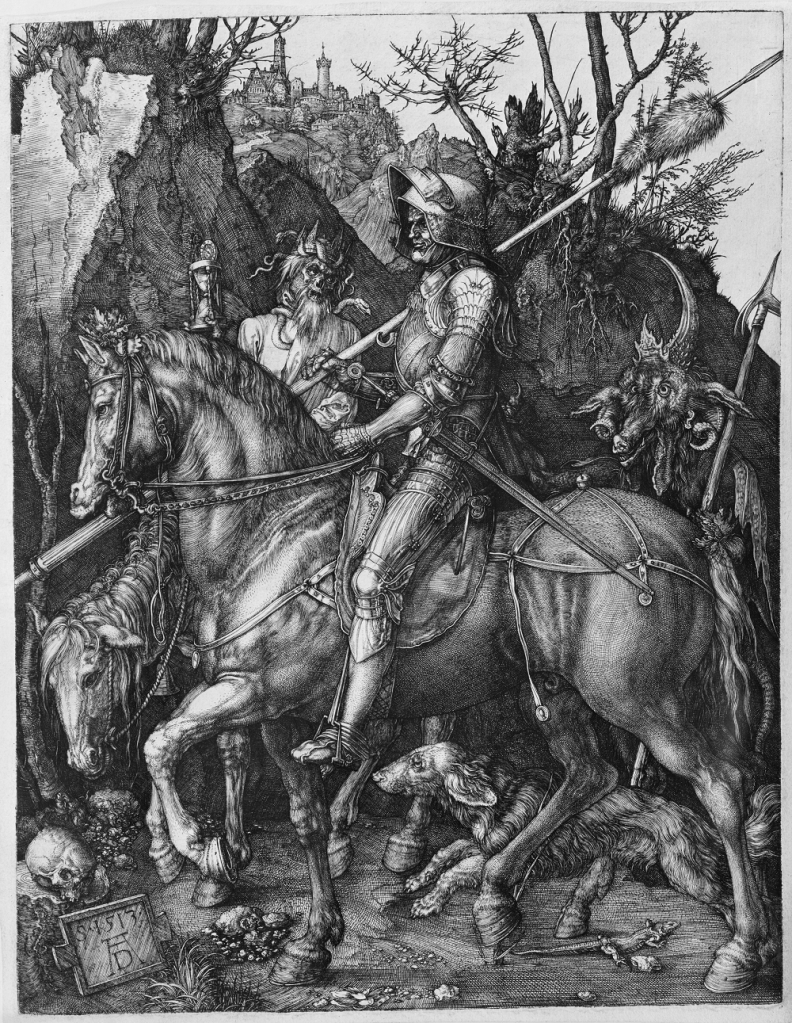

The pinnacle of Dürer’s humanist thought, however, is found in the artist’s most famous copper engraving, Melencolia I that, along with the also famous Saint Jerome and The Knight, Death and the Devil, constitute what has been known as Dürer’s three Meisterstiche (“master prints”). In general, simple terms, it has been thought that the Knight symbolizes the energetic, active decision of Christians; Saint Jerome is the thinker who finds satisfaction in his life through Christian metaphysical speculation; and Melancholy expresses the problem of apathy and discouragement on the one hand, and on the other the peace that deep wisdom confers.

In Melencolia I we contemplate a winged figure, seated next to an unfinished building, whose head rests on her left hand in a pensive attitude, while her right hand rests on a book and holds a compass. Alone and self-absorbed, surrounded by symbols of scientific principles and craft instruments, she represents human research. All the activities and all the trades of the instruments scattered on the ground are subject to melancholy. The compass in the hand of the symbolic figure aims to demonstrate that geometry, the science of measurement, and mathematics depend on the influence on melancholy. When we look at this print today, we surely don’t understand its many symbolisms, for which Dürer probably took advice from Pirckheimer. Can we say that Dürer’s character and manner of being were probably close to those of Melancholy?… We could think that this print is, in a way, his inner self-portrait: the image of a creative man, exposed in his loneliness and sadness, to doubts and uncertainties. Dürer himself said: “… but I don’t know what beauty is.” The hopelessness of this winged figure illustrates both the dangers and the satisfactions of intellectual investigation and is the image of the creative spirit, of man alone with himself. The building with the stairs indicating that it is unfinished, the problem unresolved, the winged Cupid on the stopped mill wheel, the broken bell, the hydrophobic dog, the clock with the sand falling, the empty scales oscillating, everything seems to plunge Melancholy into despair. But the magic board on the wall has 16 squares whose numbers add up to 34 in all directions, predicting a favorable solution. In addition, it includes 1514, the date in which the work was produced.

It is believed that Knight, Death and the Devil represents an allegory on Christian salvation. An armored knight is riding a haughty, walking horse along a desolated landscape, accompanied by his loyal hound, totally undistracted either by the skeletal figure of the Death who is standing in front of him on a docile horse with his hour-glass, or by the Devil, a goatlike creature with various horns, standing behind him. In the background, afar and in atop a hill, the road leads to a castle, where we can guess the rider is heading. A skull, a reminder of death, rests on a tree stump in the lower left foreground, and a lizard (sometimes interpreted as a symbol or presage of danger) crawls to the right. This engraving is dated and signed by the artist. On a tablet at the bottom left is scribed “S. (meaning “Salus“, in the year of grace) 1513” and Dürer’s monogram. The composition of the horse and rider seem to have derived from the canon of proportions drawn up by Leonardo da Vinci.

The engraving of St. Jerome in his Study seems to stress the contemplative rather than the active aspect of Christian life. Dürer presents us the translator of the Bible deep in thought at his lectern in his studio next to a large window through which sunlight bathes his figure and the room. In front of St. Jerome, in first plane, are the resting figures of his faithful lion and dog, the dog deep in sleep, the lion apparently still alert. A skull on the windowsill and an hourglass above the saint remind us of the transience of life. In his last of the three master engravings, we can appreciate how Dürer placed particular emphasis on the subtle differentiation of the material qualities of the objects. He also took great care in the depiction of the interior following to the laws of central perspective, the converging lines of which end in the space to the right of the figure of the saint. The astonishing advance in Dürer’s printmaking technique is evident when this engraving is compared with his early woodcut of the same subject, more medieval in conception. According to the diary of his trip to the Netherlands during 1521, Dürer sold or gave away copies of this print more frequently than of any of his others.

Parallel to Melencolia I and St. Jerome in his study, Dürer drew in 1514 a penetrating portrait of his aging mother (Berlin). The image was captured two months before her death. The extreme naturalism of the portrait reflects the hard life she had to endure, as she suffered from various illnesses and had given birth to 18 children, only three of which survived. In the Middle Ages “ugliness” was equated almost exclusively with evil or death, but here for Dürer it functions as a very personal way to record the features of a sitter as well as his/her inner feelings. Naturalism and the need for absolute authenticity excused here Dürer from any aesthetic recreation, even if the subject was his own mother, in order to achieve this intense, deeply emotional study, which is in turn a profound study of old age.

Apart from short trips, for example to Augsburg, Bamberg or Switzerland, in the company of Willibald Pirckheimer and the Nuremburg patrician Martin Tucher, Dürer undertook only three trips important for his artistic development: two visits to Italy and one trip to the Netherlands. In June 1520 he was with his wife, Agnes, in the Netherlands. The real reason for the trip was to ratify in Antwerp by Charles V, the pension granted to him before by Emperor Maximiliam. His travel diary gives us an account of the stops along the way, meetings and impressions. In addition to this text, various drawings of landscapes, portraits, etc. accompany his thoughts. This trip became the greatest artistic event of Dürer’s last years, already a mature and famous artist. He met the most famous Dutch painters living at the time, visited cities known for their wealth and prosperity: Antwerp, Mechelen, Brussels, Bruges, and Ghent. He became acquainted with the works of the masters of the 15th century, such as Van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden and Hugo van der Goes, and was moved by those of Lucas de Leyden, Jan Provost, Joachim Patinir and Quentin Matsys, all leaving their mark on his late works with their surprising pictorial technique, the style of their compositions, and their coloring technique.

Dürer painted a Saint Jerome (Lisbon) for the Portuguese merchant Rodrigo Fernandez d’Almada, whom he had already portrayed in an ink drawing in 1521. This magnificent religious painting is the first work, since 1520 or 1521, where the influences of Dutch art are combined with his own experiences and findings. Dürer made several studies to prepare this composition. The Study of a Man Aged 93 (Vienna) is from the best of the artist’s mature period and became a study for Saint Jerome. In both works, with the greatest realism and deep psychological penetration, Dürer created a prodigious wealth of forms; the curls of the beard and the modeling of the wrinkles come to evoke, under the visible surface, the true grandeur and serenity of this old man. The painting’s coloring is sumptuous and marvelously nuanced. The figure of Saint Jerome is based on a Dürer’s drawing of an old bearded man in which he inscribed: “The man was 93 years old and yet healthy and strong in Antwerp.” In the painting, St. Jerome, who bears the wrinkled features of the 93 year-old man drawn by Dürer, rests his right hand against his head, in a contemplative pose. With his index finger of the left hand he lightly touches the skull, a symbol of the brevity of life. The skull is symbolically placed between the open Bible on a small lectern and the ink-well, a reminder of the saint’s role as the translator of the Bible. The aged St. Jerome looks out of the picture. Dürer’s painting was strongly influenced by Flemish art, particularly the work of Quentin Matsys. It is a masterpiece from Dürer’s best pictorial period: the mastery of the line that twists in the curly beard, the volumes that stand out in perspective (like the books or the skull), and above all the psychological force of the tired expression of the old man.

At the end of his life, Dürer devoted himself intensely to the publication of his theoretical works: in 1525 was published Four Books on Measurement, two years later the Various Lessons on the Fortification of Cities, Castles, and Localities, and in 1528 the Four Books on Human Proportion. These works, carriers of new impulses, greatly influenced his contemporaries. In the Four Books on Measurement (the first book for adults on mathematics in German, as well as being cited later by Galileo and Kepler), a work to which he dedicated 16 years of his life, Dürer intended to create a treatise for the artists of his time, compiling the basic concepts of mathematics, as well as detailed explanations of applied geometry and stereometry. The Various Lessons on the Fortification of Cities, Castles, and Localities was the first printed theoretical explanation of this subject and originated from multiple suggestions.

As we have already said, Dürer dealt with the construction and proportions of the human figure from around the year 1500, posing the problem of the beauty of the human body expressed in measurable dimensions. In principle he had planned a theory of painting in which his work on proportions was not going to be more than one chapter. Given the length of this chapter, Dürer decided to delve deeper into these problems and to publish the ‘Human Proportion‘ separately. In it he developed a system endowed with scientific bases, in his treatise on human proportions the foundations of descriptive geometry were laid; in the course of his theoretical studies he moved from the search for the single ideal of beauty to the “theory of variety in perfection”, published posthumously in 1528, shortly after his death. His work was published in Latin in 1523 and 1534, in French in 1557, in Italian in 1591, and in Dutch in 1622.

Albrecht Dürer died on April 6, 1528 at the age of 56 possibly from complications of malaria. He was buried in the family mausoleum of his wife’s parents in the St. John’s Cemetery in Nuremberg. In the Nuremberg book of illustrious deaths (Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum), sheet “von mitvoch nach invocavit bis uff mitvoch nach Pfingsten” (from March 4 to June 4, 1528), it states: “Albrecht Dürer, painter at the Zystlgasse” and, added by another hand, “the famous artist”. Willibald Pirckheimer said in his lament for his friend’s death (printed in the edition of Dürer’s Four Books on Human Proportion, published on October 31, 1528) that “death had taken away everything but his glory”, and that “it would last as long as Earth existed”.

Towards the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th, there was a revival of Dürer’s work as a source of inspiration for the new generation of artists: his books were cited, works inspired by his style were produced and, above all, they were enthusiastically collected. Royalty as well as bourgeoisie, especially in Nuremberg, were avid collectors of his works, all proud to have one or more of Dürer’s works in their collections.

The first anniversaries of his death and birth were celebrated with enthusiasm, but it was the German romantics of the 19th century who popularized him. His large house in Nuremberg, where his studio was also located, remains a prominent landmark of the city and a museum, still much visited to this day. Albrecht Dürer was the first artist to whom a public monument was erected (1840), proclaiming him “the father of German art.”