Memorable temples of Ancient Egypt include those of Hatshepsut, Gourna, Ramses II (built on the left bank of the Nile west of Thebes, also called the Ramesseum), and finally, the temples of the right bank of the Nile called Karnak and Luxor both dedicated to Amun and united in antiquity by a monumental avenue. These buildings were the real centers of religious and political activity of the Theban Empire.

The difficulty of describing an Egyptian temple was initially noticed in antiquity by Greek polygraphs as Herodotus and Strabo. In fact, the Greek names of pylons*, hypostyle halls*, and obelisks* (which they applied for the first time in their brief descriptions) are still the terms we use these days. An Egyptian temple was always arranged in the same way. The temple was reached by the avenue of the sphinxes immediately followed by the first pylon. The sphinxes of Karnak’s Avenue had lion’s body and ram’s head, and between their front legs stood the pharaohs figures. They were the symbol of Amun*, the synthesis of Ra and Harmakhis* the two ancient sun-gods of the Nile Delta. Crossing the door was the first courtyard, a public place where anyone could enter. Passing through this first courtyard was a room dedicated to the ceremonies, this large room is usually called the hypostyle hall because of its construction with columns. At the bottom of the hypostyle hall was the entrance to the naos*, or holy place, reserved for the priestly community. After the naos was a second courtyard in the bottom of which were the offices, warehouses, and rooms of the guardians of the sanctuary. The whole temple was enclosed in a rectangle formed by a double wall with a corridor that completely isolated it from the exterior. As we see, there was only a succession of three elements: the pylon, the courtyard and the hypostyle hall. We will describe, therefore, each one of them.

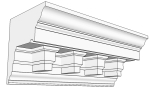

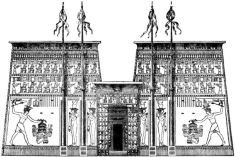

The pylon, which is the triumphal gate (with no other utility than purely decorative) had two solid square towers on each side. The large flat surfaces of the inclined walls of the pylon’s towers were decorated with reliefs representing episodes from the life of the Pharaoh who led the construction of the building. The pharaoh was also represented by large figures situated on both sides of the door. To further enrich this entrance, sometimes the Egyptians added granite obelisks carved in one piece of stone. The pylon’s square towers were topped with the only cornice* of Egyptian construction known as the inverted gorge (Egyptian gorge*). Sometimes, instead of the two great monolithic obelisks there were two gigantic columns on each side of the door which also served as decorative elements.

The courtyards sometimes had no columns surrounding them. Some other times these columns were arranged in one or two rows but only along the sides. Finally it was possible to find instances where the columns formed a real cloister* on the four sides of the open area. The first courtyard of Karnak had in the center, from door to door, two monumental colonnades which served as an avenue in the middle of the vast squared courtyard. Some of these courtyards were decorated with a row of colossi* along the two lateral walls as can be seen in Karnak and the Ramesseum. When columns were on the four sides of the courtyard sometimes they weren’t all of the same order (or type); for example, the ones located at opposite sides had bell-shaped capitals, while the other two had lotus flower buds capitals. As a general rule, as happened in Luxor, columns at the four sides of the courtyard were of similar shape. These courtyards should had free access to the people. They were the antechamber to the sanctuary itself and they will come to represent the cloister or narthex* of the later Christian church. The authentic worship was celebrated in the hypostyle hall which came immediately after the courtyard and was not accessible to the common citizens.

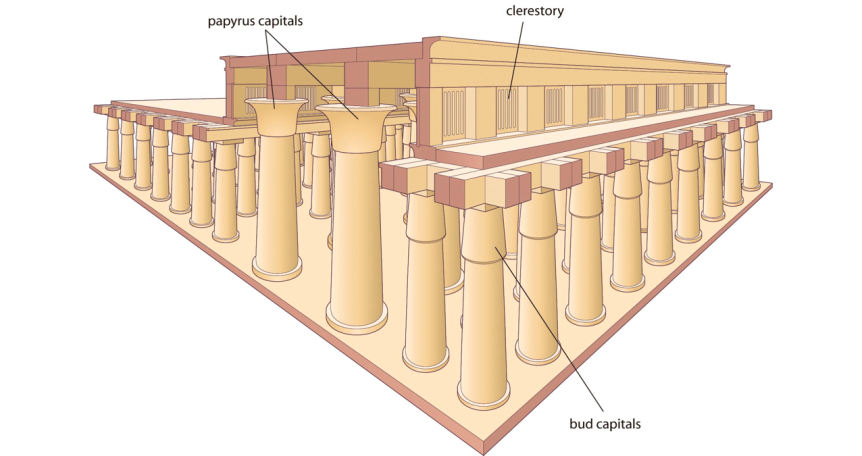

The name hypostyle hall is of Greek origin and means colonnaded hall. The hypostyle hall received light from above. This was achieved by dividing the hall into naves* (or aisles) by using rows of columns which were bigger and taller in the central nave and shorter columns supporting the roof of the lateral naves. The difference in elevation of these naves leaved a space in the ceiling through which light entered through as if there were high lateral windows. A hypostyle hall was thus a large hall supported by columns with a flat roof consisting of large lintels, and with the central nave higher than the laterals and covered with blocks of rock. These hypostyle halls had no windows on the walls, but had lighting coming from the ceiling. The Egyptian temples’ hypostyle halls were always decorated with bright polychrome reliefs and were surely the masterpiece of Egyptian construction and art. The Great Hypostyle Hall of Karnak is still the largest stone covered hall in the world. It is 152 meters long by 51 meters wide with 134 columns that supported the roof. A Gothic cathedral might well fit within this hall whose construction begun in the reign of Sethi I and was completed by Ramses II. This colossal work of the pharaohs of the XIX Dynasty is the biggest religious space built by men of any epoch or country.

The sanctuary itself was located in a second room and sometimes after another smaller courtyard. The sanctuary was the quintessential holy place where perhaps only the Pharaoh and the high priest could enter, and was the place in which the deity’s image was kept. Along the main axis of the ancient Egyptian temple, its courtyards and rooms were reducing in size. Thus, at the level of the sanctuary, the ceiling was lower, the ground level was risen, and the light was dimmed: all these features had the purpose of preparing the mind before entering into the hidden place where the divine fetish was. In this secret place, inside the temple, there were anthropomorphic statues of the god alongside magical relics.

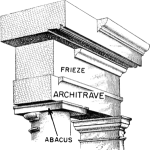

The Egyptian column included a variety of forms that coexisted at all times during the history of Ancient Egypt: the square pillar in the temple of the Sphinx has been widely found in Upper Egypt and the columns with flat facets were also found there in abundance. The capitals in the form of lotus flowers or papyrus found in the courtyards of Luxor and Ramesseum at Thebes had their predecessors in the columns of the Old Empire. There were some preferred column types used during the Old Empire like those with palm shaped capitals, whereas other complicated capital designs were a more recent invention and were mostly used during the time of the last pharaohs. The Osirian pillars, or columns in the form of Osiris shrouded with divine emblems which we can observe in the Ramesseum, seem to have been mainly built during the rule of the Ramessides. A typical characteristic of the Egyptian column is the complete absence of plinth (the base of a column) which is reduced at most to a simple ring bearing little elevation so that the column appears to rest directly on the ground. The charm of the temple of Luxor, built under Amenhotep III during the 15th century BCE, comes from its wonderful columns in form of papyrus. These columns resemble bundles of papyrus stems collected in a collar below the capital. The capital widens into a mighty ‘chalice’ bearing the weight of the architraves* (the lintel or beam that rests on the capitals of the columns). These graceful columns make Luxor one of the finest pieces of architecture of Ancient Egypt. Karnak beats Luxor by its size, Luxor beats Karnak by its beauty.

__________________________

Amun: A major ancient Egyptian deity. During the 16th century BCE his cult acquired national importance, expressed in his fusion with the Sun god, Ra, as Amun-Ra or Amun-Re. Amun-Ra retained chief importance in the Egyptian pantheon throughout the New Kingdom (with the exception of the reign of Akhenaten). Amun-Ra in this period (16th to 11th centuries BCE) held the position of transcendental, self-created creator deity “par excellence”, he was the champion of the poor or troubled and central to personal piety. His position as King of Gods developed to the point of virtual monotheism where other gods became manifestations of him. With Osiris, Amun-Ra is the most widely recorded of the Egyptian gods.

Amun: A major ancient Egyptian deity. During the 16th century BCE his cult acquired national importance, expressed in his fusion with the Sun god, Ra, as Amun-Ra or Amun-Re. Amun-Ra retained chief importance in the Egyptian pantheon throughout the New Kingdom (with the exception of the reign of Akhenaten). Amun-Ra in this period (16th to 11th centuries BCE) held the position of transcendental, self-created creator deity “par excellence”, he was the champion of the poor or troubled and central to personal piety. His position as King of Gods developed to the point of virtual monotheism where other gods became manifestations of him. With Osiris, Amun-Ra is the most widely recorded of the Egyptian gods.

Architrave: The lintel or beam that rests on the capitals of the columns. It is an architectural element in Classical architecture.

Architrave: The lintel or beam that rests on the capitals of the columns. It is an architectural element in Classical architecture.

Clerestory: A high section of a wall that contains windows above eye level. The purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both. Usually a clerestory is located on the walls of the tallest nave of a church or temple above the rooflines of the lower aisles or naves, and is covered with windows to allow light into the building.

Clerestory: A high section of a wall that contains windows above eye level. The purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both. Usually a clerestory is located on the walls of the tallest nave of a church or temple above the rooflines of the lower aisles or naves, and is covered with windows to allow light into the building.

Cloister: A covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church was commonly against a southern flank and is usually an indication that it was once part of a monastic foundation.

Cloister: A covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church was commonly against a southern flank and is usually an indication that it was once part of a monastic foundation.

Colossus: (pl. Colossi, from the Ancient Greek). A giant statue much larger than life.

Colossus: (pl. Colossi, from the Ancient Greek). A giant statue much larger than life.

Cornice: (from the Italian cornice meaning “ledge”). Any horizontal decorative molding that crowns a building or furniture element – the cornice over a door or window, for instance, or the cornice around the top edge of a pedestal or along the top of an interior wall. The function of the projecting cornice of a building is to throw rainwater free of the building’s walls. Usually, a cornice has a decorative aspect to it.

Cornice: (from the Italian cornice meaning “ledge”). Any horizontal decorative molding that crowns a building or furniture element – the cornice over a door or window, for instance, or the cornice around the top edge of a pedestal or along the top of an interior wall. The function of the projecting cornice of a building is to throw rainwater free of the building’s walls. Usually, a cornice has a decorative aspect to it.

Egyptian Gorge: The characteristic cornice of Ancient Egyptian architecture, consisting of a large concave molding with a curvature of near a quarter circle and decorated with vertical leaves and a roll molding below.

Egyptian Gorge: The characteristic cornice of Ancient Egyptian architecture, consisting of a large concave molding with a curvature of near a quarter circle and decorated with vertical leaves and a roll molding below.

Harmakhis: Also known as “Horus of the Horizon,” was an ancient Egyptian god that personified the rising sun and that also symbolized resurrection and eternal life. Though sometimes represented as a falcon-headed man wearing a variety of crowns or sometimes as a falcon-headed lion or a ram-headed lion, his most famous representation was as the Sphinx of Giza, a vast man-headed wearing the royal headdress and the uraeus. Harmakhis was considered to be not only the sun god as Horus, but also the repository of the deepest wisdom.

Hypostyle Hall: A hall or big room whose roof is supported by several columns.

Hypostyle Hall: A hall or big room whose roof is supported by several columns.

In situ: A Latin phrase that translates literally to “on site” or “in position”. It means “locally”, “on site”, “on the premises” or “in place” to describe an event where it takes place, and is used in many different contexts. In art, in situ refers to a work of art made specifically for a host site, or that a work of art takes into account the site in which it is installed or exhibited. The term can also refer to a work of art created at the site where it is to be displayed, rather than one created in the artist’s studio and then installed elsewhere (e.g., a sculpture carved in situ). In archaeology, in situ refers to an artifact that has not been moved from its original place of deposition.

Naos: (Naos, Greek word for temple; cella in Latin). The sanctuary, the innermost chamber of a temple.

Narthex: An architectural element typical of early Christian and Byzantine basilicas and churches consisting of the entrance area, located at the west end of the nave, and opposite the church’s main altar.

Narthex: An architectural element typical of early Christian and Byzantine basilicas and churches consisting of the entrance area, located at the west end of the nave, and opposite the church’s main altar.

Nave: The central part of a temple or church, intended to accommodate most of the congregation. The main space of a temple or church.

Obelisk: A tall, four-sided, elongated and narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. These were originally made by Ancient Egyptians who called it “tekhenu”. The Greeks who saw them used the Greek ‘obeliskos’ to describe them, and this word passed into Latin and then English.

Obelisk: A tall, four-sided, elongated and narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. These were originally made by Ancient Egyptians who called it “tekhenu”. The Greeks who saw them used the Greek ‘obeliskos’ to describe them, and this word passed into Latin and then English.

Pylon: The monumental gateway of an ancient Egyptian temple. It consisted of two towers, each topped by a cornice, and joined by a less elevated section which enclosed the entrance between them. In ancient Egyptian theology, the pylon mirrored the hieroglyph for ‘horizon’ or akhet, which was a depiction of two hills “between which the sun rose and set.” Consequently, Pylons played a critical role in the symbolic architecture of a temple which was associated with the place of recreation and rebirth.

Pylon: The monumental gateway of an ancient Egyptian temple. It consisted of two towers, each topped by a cornice, and joined by a less elevated section which enclosed the entrance between them. In ancient Egyptian theology, the pylon mirrored the hieroglyph for ‘horizon’ or akhet, which was a depiction of two hills “between which the sun rose and set.” Consequently, Pylons played a critical role in the symbolic architecture of a temple which was associated with the place of recreation and rebirth.